How The Humble Pencil Conquered The World

From sticks of graphite wrapped in string to mechanical pencils made of gold, centuries of innovation went into crafting the perfect writing utensil.

The pencil isn't just for the SATs. It is the go-to drawing tool of the carpenter and the architect, the cartoonist and the painter. We used pencils when we learned math in elementary school, and a graphite-filled piece of wood remains the implement of choice for anyone who needs to make a mark that is not permanent.

The pencil's journey into your hand has been a 500-year process of discovery and invention. It began in the countryside of northern England, but a one-eyed balloonist from Napoleon Bonaparte's army, one of America's most famous philosophers, and some of the world's most successful scientists and industrialists all have had a hand in the creation and refinement of this humble writing implement.

Sharpen your trusty no. 2 and get ready to take some notes. This is the story of the pencil.

Write This Down

Sometime in the 16th century, a tree fell over in Borrowdale, England. Under that tree was an igneous rock layer with protruding veins of a dark gray metallic-looking substance. The locals noticed that it looked just like lead. But this was no metal. It was pure carbon. It was graphite.

Chemistry was a young scientific field in the 1500s, so the locals couldn't have known exactly what they found. They did notice one crucial fact about the new material: the graphite made a darker mark on paper than lead, which had been used in styluses since Roman times. So they called it black lead. English people cut graphite into chunks and put it into sticks that could be used to write. They wrapped the sticks in paper or string and sold them on the street. This new tool was called the pencil—a name derived from pencillum, the Latin for a fine brush. Making your mark would never be the same.

Nothing was like the pencil. It was completely dry. You didn't have to worry about spilling ink like you did with a quill pen. It made that dark, discernible mark on paper. And it was erasable! Although the pink rubber erasers we know today wouldn't be attached to pencils until 1858, people figured out long before that you could rub out pencil marks with bread crumbs.

History gets a bit uncertain when when you go back five centuries, but it is believed that in the 1600s, a woodworker in Keswick, England, first came up with the idea of enclosing black lead in wood. A rectangular wooden stick was chopped in half lengthwise. A groove was then cut into one of the halves to make room for a slim stick of black lead. The three pieces—the black lead and the two halves of wood—were glued together with the black lead inside. The result was a rectangular writing implement and the world's first wooden pencils.

This was a big deal. Wood was sturdier than paper or string, which needed to be unraveled as the black lead wore down. The new casing, probably cedar, could be carved and sharpened with a knife as the black lead shortened. Thus the phrase "sharpen your pencil" was born.

Not long after its discovery, black lead shot up in value—it was used as an ingredient in making cannonballs as well. The English government wanted in on the profits. It took control of the Borrowdale black lead deposit and set up mines around town with notoriously strict oversight; workers were searched at the end of each day to prevent illicit sales. By 1752, the government passed a law declaring the theft of black lead a felony.

Black lead deposits were subsequently found elsewhere around Europe, but the English mines produced the hardest and darkest black lead in the world. Its quality was so superior that England became the leading pencil and graphite producer. The government took rigorous efforts to conserve its black lead supply, only mining for about six weeks every five years to avoid extracting too much of the precious material, according to Henry Petroski's The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance.

By the late 1700s, the old-fashioned lead-alloy stylus was hardly used. Other than the pen, which stuck around because of its advantages over the pencil in elegance and permanence, black lead became the go-to writing tool. Pencil-makers started calling it simply "lead," which is the reason people still talk about pencil "lead" even though the graphite inside their no. 2 is nothing of the sort. Other terms would pop up as well, namely "plumbago," derived from plumbum, the Latin term for lead. This name would stick throughout the 1800s, until people started calling the crystalline carbon substance "graphite," a word derived from the Greek term graphein, meaning "to write."

The Birth of the Modern Pencil

England's reign as pencil king waned in the 1790s. The Borrowdale mines were running out of graphite. The country went to war with France in 1793. This conflict—a prelude to the Napoleonic Wars—would change the world map and the global balance of power, but not before it shook up the pencil industry.

At the dawn of the fighting, England imposed an embargo on France, which had been one of the primary importers of English pencils. While it may have made sense militarily, the embargo had a nasty side effect on England's commerce. France suddenly suffered a shortage of pencils and graphite. A year after the war started, French Minister of War Lazare Carnot commissioned scientist and military commander Nicolas-Jacques Conté to find a solution.

At the time, Conté was working on military uses for the newly invented hot air balloon, an effort that cost him his left eye when a balloon experiment resulted in an explosion. Conté had to push the balloon project aside to find a new way to make pencils. That meant either finding a substitute for graphite or coming up with a suitable mixture of graphite and another substance. The story goes that it took the inventor just a few days to come up with an answer.

Conté's mixture had two main ingredients: ground-up graphite and clay. He mixed the two with water and let them harden in rectangular molds so they could be fired in a kiln. Conté noticed he could manipulate the lightness or darkness of the lead by varying how much clay was used. More clay made for a harder pencil lead and a lighter mark on paper. Less clay meant a softer lead and a darker mark. To encase the lead in wood, Conté cut a groove out of an entire wooden stick, rather than first cutting a stick in half like the English did. The pencil lead was glued into the groove, and another piece of wood was glued on top of the lead.

Conté's pencil was patented in 1795. While England's pure-graphite pencils were still popular, Conté's pencils would become the ideal design for manufacturers to emulate by the mid-1800s. This invention spurred by necessity became a handy way to create specialized pencils for writers and artists who wanted different shades of lead.We still use Conté's graphite-clay mixture idea today.

A Philosopher Makes His Mark

After Conté, France sat atop the pencil pile. Companies around Europe heard about the mixture but struggled to reverse-engineer the secret system and began experimenting with alternatives.

Across the Atlantic, Americans had already been playing with mixtures of materials because of England's dwindling graphite supplies and the trade troubles caused by the War of 1812. Americans used all sorts of ingredients. The family of Walden author Henry David Thoreau, for instance, mixed graphite with bayberry wax or spermaceti, a wax from sperm whales commonly used to make candles at the time.

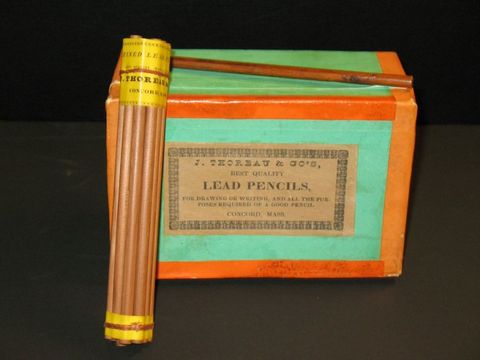

The Thoreau pencil company was founded in Concord in 1821, shortly after Thoreau's uncle found a graphite deposit in Bristol, NH. Two years later, Thoreau's father took over the business and named it John Thoreau & Company. His pencils weren't of Conté quality, but Thoreau's wax and graphite mixture was one of the best pencil leads available in the U.S. Long before he was living alone or writing transcendentalist literature, Henry David Thoreau spent his childhood helping his father make pencils. He would make his lasting mark on the family business came in the 1830s

A young man and recent Harvard University graduate, Thoreau had just resigned from a teaching job because he did not want to impose corporal punishments. Needing something else to occupy his time, the budding philosopher set out to perfect his family's pencil leads. It's likely that Thoreau had little to no knowledge of Conté's method, according to Petroski's book. It was probalby in an encyclopedia at the Harvard Library, then, where Thoreau came upon the idea to substitute clay for the bayberry wax and spermaceti.

Thoreau crushed graphite to different granulations to find the right consistency to produce a solid mixture with clay. The result was a pencil lead that was harder and darker than any his family had ever produced. Thoreau was effectively rediscovering what Conté had figured out 45 years earlier, but it was right on time for the family business. John Thoreau & Company profits soared by the 1840s.

Thoreau left the business to pursue his career in philosophy and writing, but would return periodically when he needed money. Again he would try to improve the business through innovation, and at one point he developed new machines to speed up the manufacturing process, including a machine for grinding the graphite. He also invented a device that could drill a hole down through the pencil lengthwise so the lead could slide inside. Walden was published in 1854, two decades after he figured the ideal recipe for pencil lead. It's said that Thoreau may have brought his family's pencils with him to Walden Pond and that he wrote at least the first chapter of the book with them. Thoreau's close friend, poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, was known to use Thoreau's pencils.

The Thoreaus' story isn't just a curious case of a literary icon playing inventor. It was emblematic of what happened to the pencil in the early-to-mid 1800s. As knowledge of Conté's mixing recipe spread around the world, competition grew, as did the demand for graphite. The Thoreaus stopped making pencils altogether in 1853 in favor of selling pure graphite. Elsewhere, the race to rule the pencil industry was sharpening.

The Million-Dollar Industry

The spread of Conté's mixing method in the mid-to-late 1800s coincided with the rise of the machines. Machinery could easily make the wooden bodies of pencils rounded or hexagonal. Small family businesses purchased factories to churn out pencils. Graphite was booming. According to Petroski's book, pencil-making became a million-dollar industry.

German and American companies rose to prominence during this period of pencil history. The German A.W. Faber company, today known as Faber-Castell, became so popular that other manufacturers fraudulently stamped "Faber" on their pencils to generate more sales. The J.S. Staedtler company, Faber-Castell's longtime German rival, made about two million pencils per year in the 1870s. In America, the Joseph Dixon Crucible Company was on its way to becoming one of the country's most iconic brands.

It was the crucible that made Dixon. He founded his company in 1827 to make these containers in which metals can be melted. It was the right market at the right time; the Mexican-American War erupted and crucibles because a hot item in 1840s, needed to manufacture weapons and other military equipment. And what were Dixon crucibles made of? Graphite.

Dixon had been making pencils on the side on a small scale even when crucibles made up most of his business. Thanks to all that wartime profit, he had enough money to begin mass production. In 1847, he set aside space in his Jersey City factory for pencil making. Dixon pencils took off in the 1870s, when the company advertised its product as American-made to capitalize on the growing domestic demand for pencils. In 1873, the company purchased the American Graphite Company of Ticonderoga to secure its own source of graphite.

That decade, the Dixon Company produced about 80,000 pencils every day. If a single pencil was missing at the end of the day, all the employees in the room were fired. Factory supervisors kept a tight watch on any visitors. With these strict manufacturing procedures, the Dixon Ticonderoga Company pumped out thousands of their distinct yellow and green pencils, making them one of today's most recognizable brands.

Improvements to the Pencil

You might think of the mechanical pencil as a modern idea, pioneered by someone who got tired of sharpening and sharpening their wooden scribblers. In fact, pencil-makers have been making "lead holders," early versions of mechanical pencils, for centuries. These lead holders were made of metal, sometimes silver and gold. As such, they were viewed as adornments through the 19th century. The weight made them difficult to use, too, so the precious-metal mechanical pencils never became very popular.

Then, in 1915, Japanese metal worker Tokuji Hayakawa invented the Ever-Ready Sharp mechanical pencil, or simply, the Eversharp pencil. It was as thin as a normal wooden pencil and the lead fit snugly inside. Rotate the metal pencil as if you were screwing it together and the lead would pop out. The design would take off around the world. Hayakawa's company would be named the Sharp Corporation after his pencil.

The other invention that shaped today's pencil happened at the other end of the implement. A couple of decades before Conté developed his pencil lead mixture, English minister and discoverer of oxygen Joseph Priestly noticed that natural rubber, a tree resin, could pick up graphite particles when rubbed against paper, and was better at it than the old bread crumb method. Because it rubbed pencil marks off sheets of paper, Priestly called his erasing tool a "rubber," which remains the common term for an eraser in the United Kingdom.

As far as we know, a Philadelphia stationer named Hymen Lipman was the first person to glue a small piece of rubber to the end of a pencil, in 1858. He patented the design, but in 1875 the courts ruled it invalid. The logic was that a pencil and an eraser didn't need to be attached in order to be used. Which is true.

With a patent out of the way, attaching erasers to pencils became the newest fad in the American pencil business. Most American pencils had pink or red erasers at the back by the 1920s. (Today these erasers are often made of vinyl, a type of plastic.) Almost everywhere else in the world, erasers have remained separate from pencils.

Write On

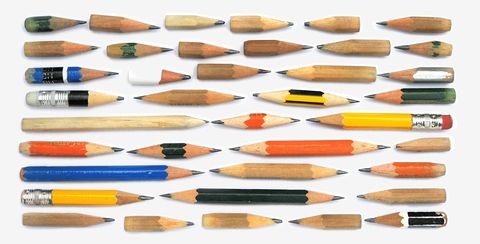

Today, pencils of every stripe are at your fingertips. Golf pencils. Colored pencils. Mechanical pencils. Carpenter's pencils, which retain the the rectangular shape of the invention's early days.

There are entire systems for classifying pencils now. European and Asian countries use a letter-based approach, with H for hard and B for black. A pencil with a 9B grade is basically pure black, a 7B slightly less so, and a 5B less than that. A 9H is a very hard pencil that makes a very light mark. The most common pencil is at the midway point: HB.

Pencils in the United States are generally graded numerically. The higher the number, the harder and lighter the pencil lead will be. The #2 pencil is our equivalent of an HB, widely preferred because of its balance. It's dark without being too smudgy, yet hard enough that it won't break too easily. This is why the trusty #2 is the required writing implement for the SAT. The #1 pencil will smear in the Scantron machine; a #2.5 or #3 will be too light for the machine to read.

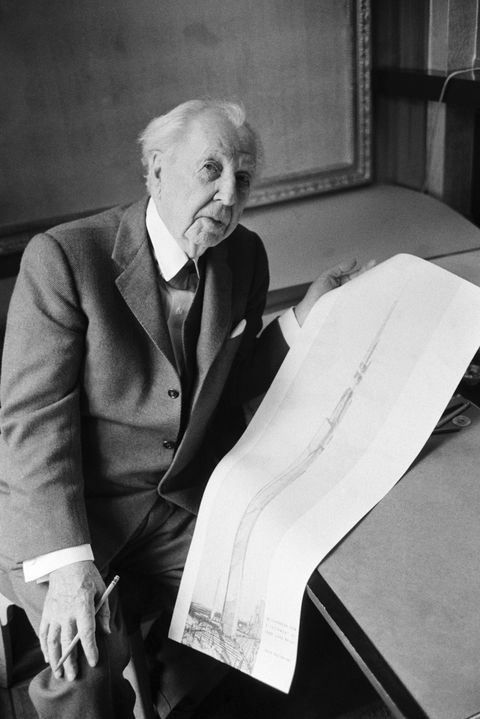

If you love the feel of a great pencil even in this age of digital everything, take heart. Some of history's most famous writers, inventors, and architects were staunch pencil users. Author John Steinbeck was famous for refusing to write until two dozen Blackwing pencils were sharpened and positioned at the ready. Thomas Edison kept a pencil in his vest pocket wherever he went. Frank Lloyd Wright has his own pencil line.

It 's a simple invention. Even today, a pencil is basically still a mineral discovered under a fallen tree that's crammed inside a stick and used to leave marks on paper. Praise the humble pencil, though, for it simplified writing, made for easy erasing, and was the device that writers and architects and scientists around the world reached for when they brought new creations and discoveries into the world.

![[Appreciation Gifts 2023] KSG set - Double Pen SET - Parker IM Rollerball & Ballpoint Pen - [Various Colours] - KSGILLS.com | The Writing Instruments Expert](http://ksgills.com/cdn/shop/files/WhatsAppImage2023-08-19at3.14.43PM.jpg?v=1764419608&width=900)

![[Appreciation Gifts 2024] KSG set - Double Pen SET - Parker IM Rollerball & Ballpoint Pen - [Various Colours] - KSGILLS.com | The Writing Instruments Expert](http://ksgills.com/cdn/shop/files/ksgills-fathers-day-gift-set.png?v=1764419608&width=1000)

![KSG set - Double Pen SET - Parker IM Fountain & Ballpoint Pen - [Various Colours] - KSGILLS.com | The Writing Instruments Expert](http://ksgills.com/cdn/shop/products/THUMBAIL_KSGGiftSet-ParkerIM-BlackGold-FP_BP-Main.png?v=1659158551&width=900)

![KSG set - Double Pen SET - Parker IM Fountain & Ballpoint Pen - [Various Colours] - KSGILLS.com | The Writing Instruments Expert](http://ksgills.com/cdn/shop/products/BlackGold.png?v=1693741987&width=1000)

Leave a comment